The Cambrian period occurred approximately 542-488 million years ago, and included the biggest evolutionary explosion in Earth’s history. Some researchers think this happened due to a combination of a warming climate, more oxygen in the ocean, and the creation of extensive shallow-water marine habitats—which, combined, made an ideal environment for the proliferation of new types of animals, including animals that were larger and more complex in their body shapes and ecologies than their ancestors.

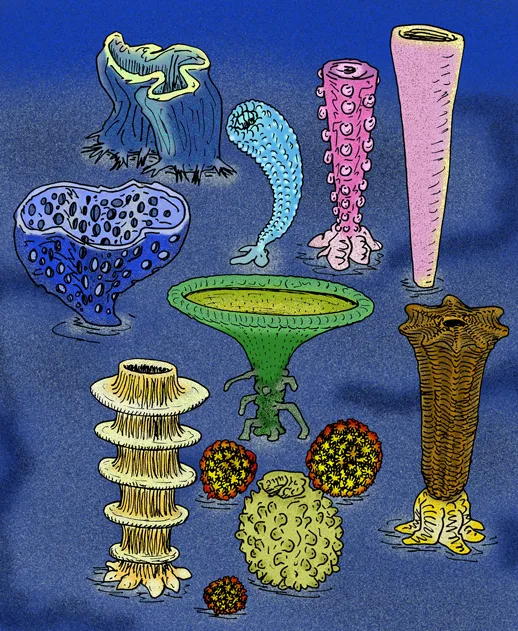

A Collection of Cambrian Fossils

When you're standing in a museum surrounded by fossils, you can almost imagine drifting through time to when long-extinct creatures swam the ocean. Found all over the world, these fossils can be read by scientists like pages from the book of the past. They tell not only an evolutionary story — the family tree of life — but also how these creatures used to live. Fossils can be found throughout the geologic history of earth, going back billions of years. Here we explore one of the most exciting of times, the Cambrian, when many of the major groups of animals familiar to us today first appear as conspicuous fossils. This is often referred to as the Cambrian Explosion.

The Cambrian Period

Credit: Smithsonian Institution

The Famous Trilobites

Credit:Hectonichus, Wikimedia Commons

Relatives of insects and crabs, trilobites originated in the Cambrian and went extinct at the end of the Paleozoic Era, some 252 million years ago. Seafloor dwellers, some would curl up like pill bugs (perhaps when threatened) while others burrowed underneath sand and mud. The over 20,000 trilobite species had many techniques for catching food, including predation, scavenging, filter feeding, and even forming a symbiotic relationship with bacteria.

The Smithsonian’s trilobite collection, with a substantial donation by Robert Hazen, an earth sciences professor at George Mason University, has more than 2,000 trilobites from six continents and all eight trilobite orders in nearly flawless condition. You can see them in the Sant Ocean Hall.

The Prickly Hallucigenia sparsa

Credit:Smithsonian Institution - Department of Paleobiology

Reconstructing how long dead creatures lived is always a challenge. The extinct Hallucigenia sparsa is notable for its peculiar appendages. It was originally reconstructed with two rows of spines on one side of its body and a row of tentacle-like structures on the other. Later it was realized that the spines were for protection and the ‘tentacles’ were legs. The new reconstruction, along with fossils from China, showed Hallucigenia to be a member of the Onycophora, or velvet worms, which today are entirely terrestrial.

Spiny Wiwaxia

Credit:Ryan Somma, Flickr

Scientists have also been unsure about the slug-like Wiwaxia corrugata, with its unique combination of spines and defensive scales on its upper surface. Could it be a mollusk, a worm, or something that does not even have any known living relatives? Like Opabinia and Anomalocaris, shown in following slides, we really don’t know what Wiwaxia was related to.

The Ferocious Hurdia victoria

Credit:Apokryltaros, Wikimedia Commons

Hurdia victoria has been nicknamed the Tyrannosaurus rex of the Cambrian era due to its large size. Some specimens reached 50 cm (around 20 inches), which was large for a time when most animals were about as big as a fingernail. Its prey consisted of the first fossil in this slideshow, the trilobite, and other smaller animals crawling on the seafloor. It had a three-part shell that extended out in front of its head like a modern-day lobster.

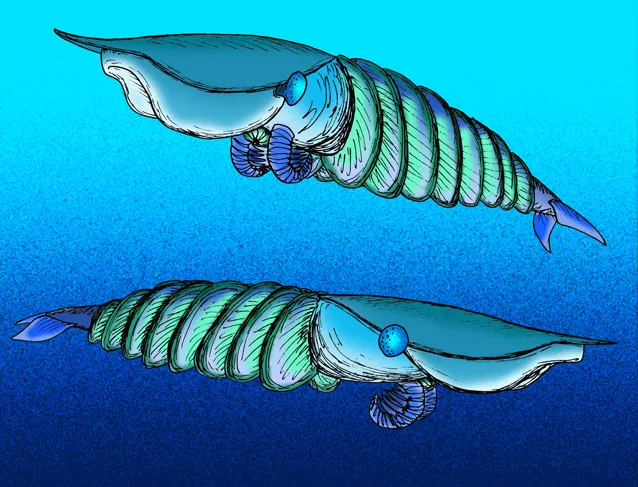

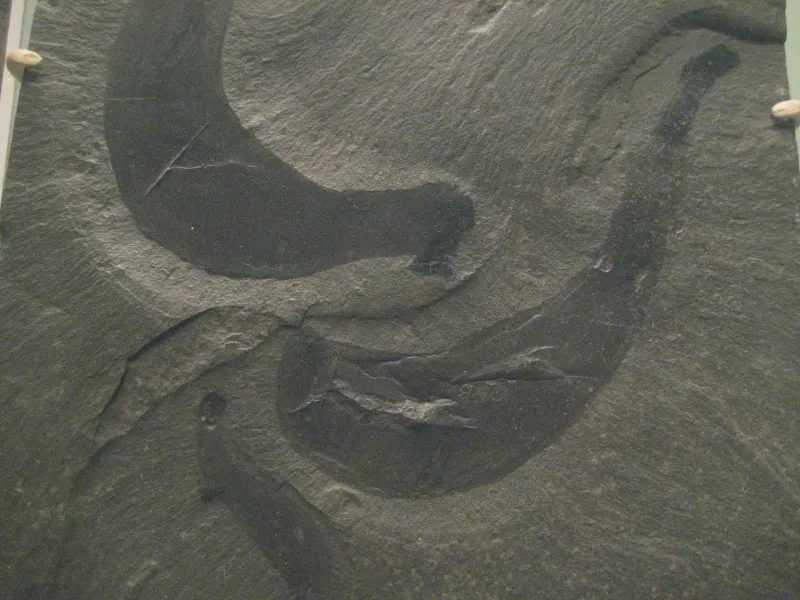

The Giant Anomalocaris canadensis

Credit:Tim Evanson, Flickr

Even larger than Hurdia victoria was Anomalocaris canadensis. This species reached almost three feet (one meter) long, and related Chinese species were probably twice this size, dwarfing the other organisms of its era. Some research suggests that Anomalocaris canadensis may have been less a fierce predator and more a gentle giant, perhaps feeding on soft prey such as worms or plankton due to its relatively weak jaw (though scientists still debate this).

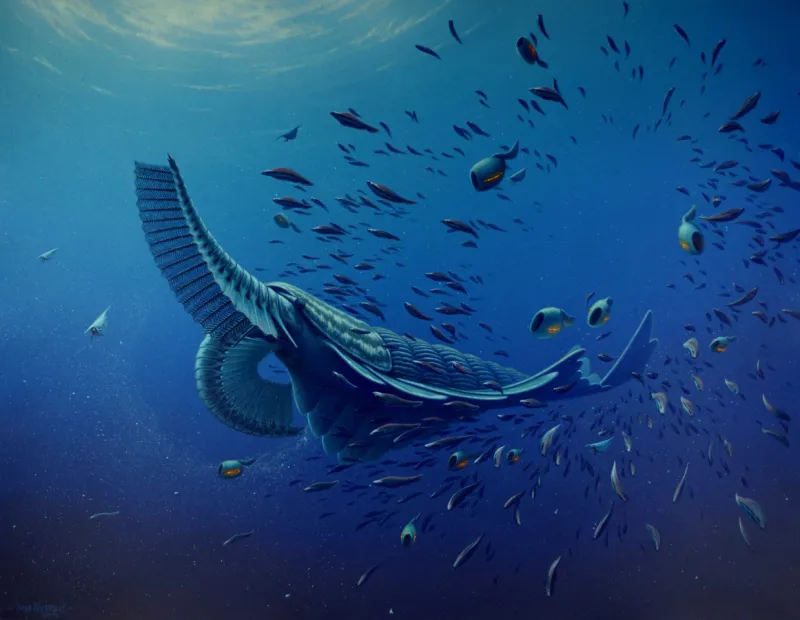

The First Filter Feeder

Credit: Bob Nicholls/Bristol UniversityToday, filter feeders like clams, sponges, krill, baleen whales, fishes, and many others fill the ocean, spending their days filtering and eating tiny particles from the water. The first known filter feeder was a large shrimp-like creature called Tamisiocaris borealis. This species is an anomalocarid—but unlike its relatives, it doesn't seem to be an apex predators, sitting at the top of the food chain and eating smaller animals. Scientists think the feather-like structures on its head were used to rake plankton from the sea. The appendages had finely spaced spines, further divided by smaller spines, which would have been efficient traps for small plankton.

The Canniballistic Ottoia prolifica

Credit:Claire H., Wikimedia Commons

The ancient worm Ottoia prolifica lived in a self-constructed home below the ocean floor that was shaped like the letter 'U.' From there, Ottoia prolifica looked for prey, which it would swallow headfirst. Most of its prey were small shelled animals related to mollusks as well as worms. Ottoia prolifica fossils have shown that cannibalism existed in the Cambrian period, since there have been portions of one Ottoia prolifica found in another specimen’s gut.

The Living Boat Haplophrentis carinatus

Credit:Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History: Department of Paleobiology

Haplophrentis carinatus had two oar-like appendages (called “helens”). These worked to keep the body stable and allowed Haplophrentis carinatus to move along the ocean bottom as it looked for food. However they couldn’t always move fast enough and were sometimes caught by Ottoia, as over 30 specimens have been found in different preserved specimens of Ottoia.

Eying Opabinia’s Adaptations

Credit:Nobu Tamura , Wikimedia Commons

Many species had adaptions that minimized their chances of being eaten by predators like Hurdia victoria and Ottoia prolifica. Opabinia had five mushroom-like eyes that allowed it to see predators approaching from many directions. Additionally, its segmented portions were filled with fluid in order to be more flexible. Its appearance is so odd that scientists laughed at the first reconstructed image.

Reef Beginnings

Credit:Apokryltaros,Wikimedia Commons

Archaeocyatha first appeared towards the end of the Cambrian explosion and may have been a kind of sponge. These once abundant sponges tended to grow close to each other and form mounds on the sea floor. These mounds created a sort of reef, making Archaeocyatha Earth’s first reef-building animals. Scientists use Archaeocyatha fossils to determine the age of different rock strata or layers.

Scientists and Fossils

Credit:California Academy of Sciences,Flickr

Fossils from the Cambrian period are found throughout the world. The Burgess Shale in Canada has long been famous for its fossils of animals from the Cambrian period, and the Chengjiang fossil site in China is famous for containing about 196 fossil species, many of which are exceptionally well preserved. Great care is taken to protect these fossils when they are collected since they can explain so much about the early evolution of animals.