Surprising Results Upon Reexamining the Curious Jaw of the Moray Eel

In morphology there is no such thing as insignificant detail; each observation, no matter how trifling, may carry the germ of an explanation for others of much greater consequence.

—Emile Baudelot (1858)

Hidden within their mouths, most fishes have a second set of jaws which we rarely see. They are nestled in the back of their throats, and responsible for extra processing of food to move it to the esophagus (the tube that connects the throat to the stomach). Like typical mouth jaws, these “pharyngeal” jaws have teeth on top and bottom. Pharyngeal teeth vary in shape depending on what the fish eats. Molar-like teeth are excellent for crushing and grinding mollusks, for example.

The pharyngeal jaws of most fishes are supported and operated by a cradle of muscles. Moray eels have muscles that are more like bungee-jumping cords, giving them the special ability to sling their pharyngeal jaws forward and backward. Moray teeth are sharp and curved, helping them hold onto large prey—other fishes, octopods, squids, and crabs.

Why would moray eels need such a mobile, and slightly creepy, pharyngeal jaw? Ichthyologist Gareth Nelson in 1967 was the first to meticulously dissect and diagram the muscles around moray eel jaws. He proposed that the arrangement of protractor and retractor muscles in the throat jaws allowed a moray to transport large prey into its long esophagus.

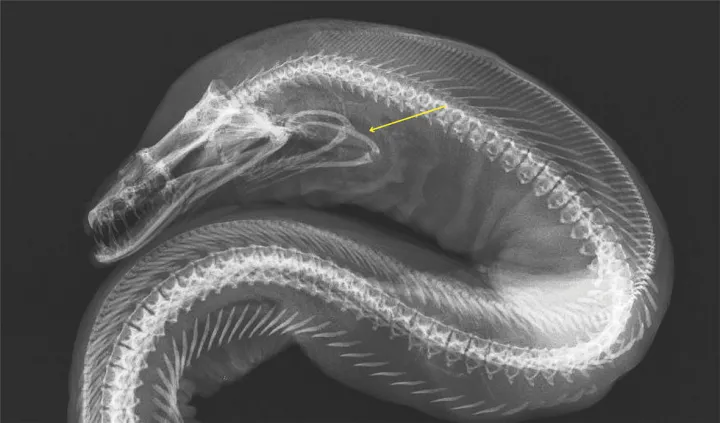

Forty years later, with advances in video technology, researchers Rita Mehta and Peter Wainwright recorded a moray eel feeding in high-speed. Dubbing it “raptorial” feeding, they documented what Nelson had suspected, that a moray’s pharyngeal jaws shot forward during feeding and then pulled back for swallowing. Their use of video fluoroscopy (a video x-ray of swallowing) confirmed that the moray’s unique pharyngeal jaw movement served to grab and transport food along its throat into its esophagus.

This feeding adaptation is vital for moray eels as they live in narrow burrows in rock crevices or caves in sandy habitats—their bodies are correspondingly long and narrow. Around coral reefs, moray eels can be seen poking their heads out to snatch passing prey and then retreating into their burrows. While other fishes suck in prey, literally expanding their mouths and throats to generate an inward suction force, moray eels typically do not have the space to expand.

Still, scientists didn’t fully understand how the moray’s special jaw functioned. In 2008, Mehta and Wainwright echoed Nelson’s original anatomical studies by dissecting moray eels and re-documenting the jaw muscles. But, as any high school biology student knows, dissection is a messy business. Muscles, bones and other structures have to be painstakingly teased apart to find every connection. The anatomical descriptions are only as accurate as the dissection itself.

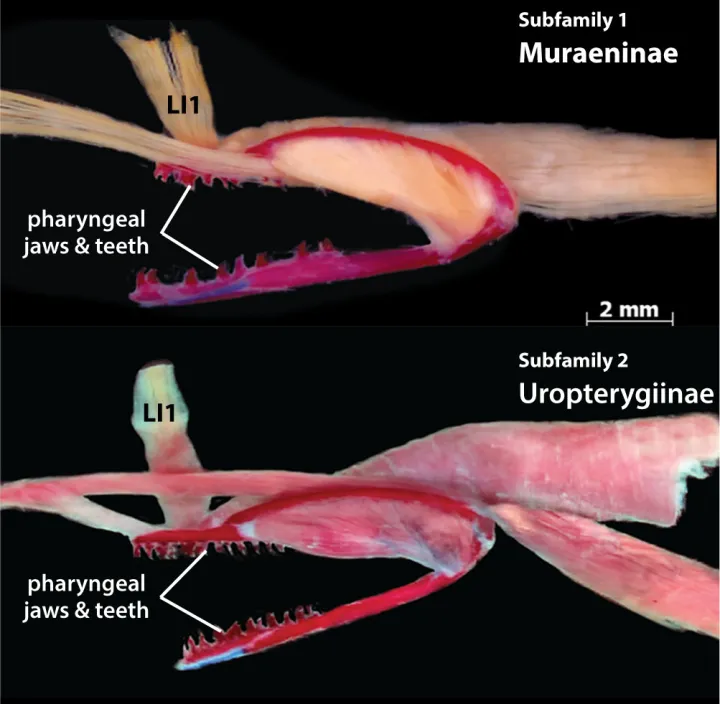

In 2019, when Dave Johnson, a research zoologist and curator of marine fishes at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, re-examined the pharyngeal jaws of moray eels, he was surprised. His staining technique, which has become a standard for looking at muscles, revealed a different picture of the jaw anatomy. The 2008 study had misidentified several muscles, and missed one entirely—a large muscle that anchors the top of the jaws to the upper body musculature (LI1 in the figure below).

Johnson’s anatomical work also found two other differences between the moray subfamilies that had been overlooked. He showed that the mechanisms used to extend and retract the pharyngeal jaws are distinct in the two moray eel subfamilies—same function but different anatomical solutions.

It has taken scientists more than fifty years to sort out the anatomy of the moray eel jaws. Johnson’s accurate description of the muscles and their attachment points finally set the stage for a deeper analysis of how the jaws operate. Now that we know the parts, it’s time to figure out how they all work together.

Studies of moray eel jaws remind us that science is progressive, and sometimes moves one step forward and two steps back. The more than 200 species of moray eels that offer a wealth of opportunities for further research. A better understanding of one group of animals also lays a foundation for insights about others. Johnson and co-author Peter Konstantinidis, examining a deep-sea telescope fish, were excited to discover a similar, but even more specialized, raptorial feeding mechanism. There is still much to be learned about the varied roles of these “extra” fish jaws in feeding.