This new species of lobster is blind—an adaptation to deep-sea life—and has very bizarre claws, or chelipeds. It was discovered about 300 meters (984 feet) deep in the Philippine Sea by a Census of Marine Life expedition. Not only was this a new species, but it was placed in an entirely new genus as well. It's scientific name,Dinochelus ausubeli, honors a co-founder of the Census, Jesse Ausubel.

Deep Ocean Diversity Slideshow

Deep sea animals have to live in a very cold, dark, and high-pressure environment where they can't see a thing! To survive there, they've evolved some very strange adapations. Some make their own light, an ability called bioluminescence, while others are totally blind. Some are terrifying looking, like anglerfish, while others are quite beautiful—even if there is no one to appreciate it except us people looking at photos. See some of the remarkable adaptations that deep-sea animals have evolved in this slideshow. Learn more about the deep sea and deep-sea corals at their overview pages, and see photos of other bioluminescent animals.

Blind Lobster

Credit: Tin-Yam Chan/COMARGE Census of Marine Life

Zoanthids on Hydrothermal Vent

Credit: Charles Fisher, Ridge 2000 Program/ChEss, Census of Marine LifeFlower-like zoanthids, relatives of coral, carpet a hydrothermal vent. This species of zoanthid is the first ever discovered at a hydrothermal vent. See more pictures of incredible deep sea diversity at our slideshow!

Yeti Crab

Credit: A. Fifis, Ifremer/ChEss, Census of Marine LifeThe yeti crab (Kiwa hirsuta), an unusual, hairy crab with no eyes, was discovered in 2005 on a hydrothermal vent near Easter Island. It represents not only a new species but also a new genus—Kiwa, after the mythological Polynesian goddess of shellfish. Learn more about the Census of Marine Life and see other species found during this 10-year project.

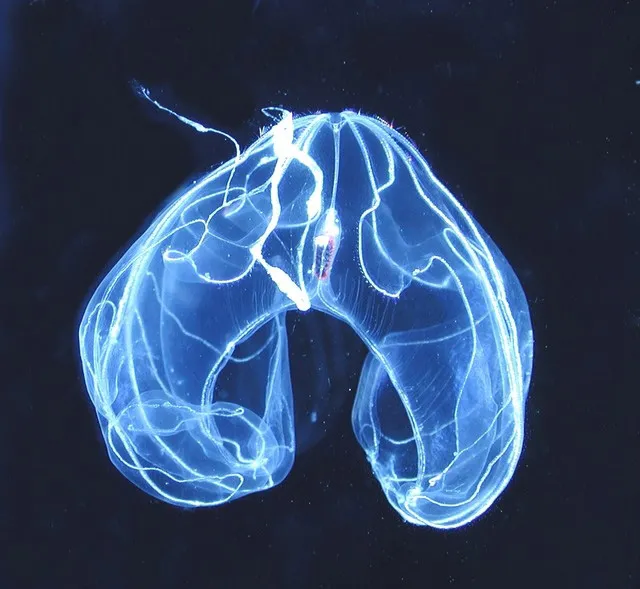

Bioluminescent Comb Jelly

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeLike many deep sea creatures, this tiny comb jelly (Bathocyroe fosteri) has a transparent body, enabling it to blend into the surrounding waters. This ctenophore is very common around the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. More about the deep ocean can be found in the Deep Ocean Exploration section.

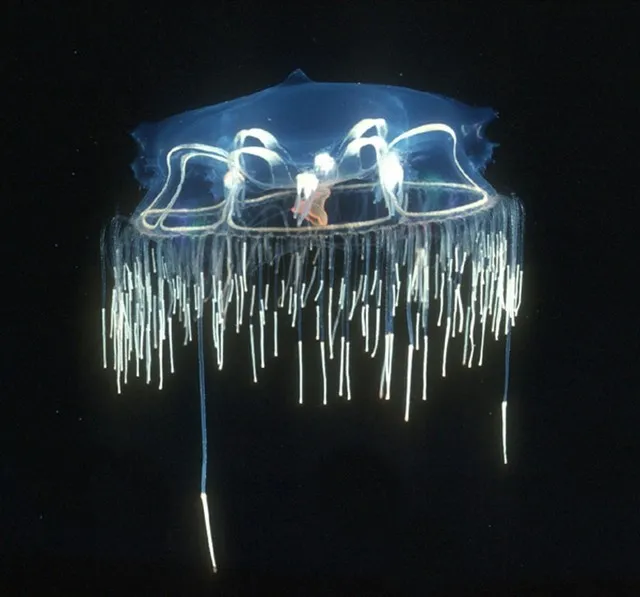

Midwater Jellyfish

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeA fringe of short tentacles surrounds the flattened bell of this tiny, transparent jellyfish (Halicreas minimum), which can be found at depths up to 984 feet (300 meters). But it would be hard to spot: the bell grows up to just 4 centimeters (2 inches) across! See more deep ocean diversity and explore more about jellyfish biodiversity.

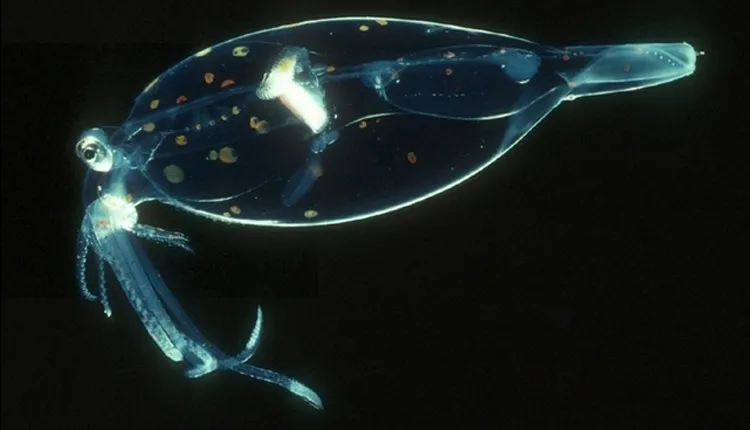

Cockatoo Squid

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeThis transparent cockatoo squid (Leachia sp.), also known as a glass squid, lives in the depths of the ocean and has many adaptations to help it survive there. It retains ammonia solutions inside its body that give it a balloon-like shape and help it float. It has large eyes and pigment-filled cells, or chromatophores, that look like polka dots and serve as camouflage.

See more pictures of bioluminescent animals that light up in the dark ocean water, and other organisms found in the deep ocean by the Census of Marine Life.

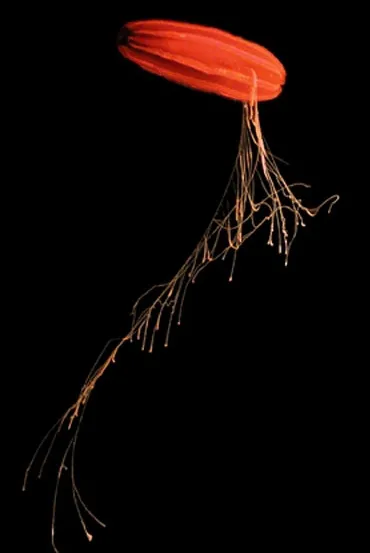

Red Mid-Water Comb Jelly

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeLike this ctenophore (Aulococtena acuminata), many animals that live in the midwater zone are red—making them almost invisible in the dim blue light that filters down from the sea surface. This small comb jelly snares prey with its two short tentacles. Read more about the deep sea and comb jellies.

Unidentified Comb Jelly

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeThis jelly’s red color provides camouflage in the deep ocean. Red light rarely reaches those depths, and most deep-sea animals have lost the ability to see red. The long, complex tentacles of this unidentified comb jelly (Order Cydippia) have sticky cells that can snag prey, and then retract. Learn more about comb jellies and click through a slideshow of deep ocean animals.

Jewel Squid

Credit: David Shale/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeThis beautiful jewel squid (Histioteuthis bonnellii) can be found swimming above the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, at depths of 500-2,000 meters (1,640-6,562 feet). The “jewels” covering the body are bioluminescent photophores. But these squids can't bargain for their lives with those jewels: they have been found in the stomachs of sperm whales, swordfish and sharks.

A Fish that Looks Like a Whale

Credit: Kunio AmaokaThis deep sea creature, the whalefish (Cetomimidae), has a whale-like body, a gaping mouth, no fins or scales and a deep lateral line, which detects vibrations in the water. The first specimens were discovered by two Smithsonian scientists in fish collections at the National Museum of Natural History more than a century ago. In the 1980s, a different scientist realized that they only had female adults in the museum collections. Where were all the males? It would take another 20 years to find out. Find out how this fish was part of an international scientific mystery.

Sea star, Captured by ROV

Credit: B. Bluhm, K. Iken, UAF, Hidden Ocean 2005, NOAAA sea star, Hymenaster pellucidus, brought up from a benthic ROV dive. View the “Under Arctic Ice” photo essay to learn more.

Big Red Jellyfish

Credit: ©2002 MBARIMarine biologists from MBARI nicknamed this startlingly large jellyfish—which grows over one meter (three feet) in diameter—"big red." It would be hard to miss, except that it lives at depths of 650 to 1,500 meters (2,000 to 4,800 feet). Big red uses four to seven fleshy "feeding arms" instead of stinging tentacles to capture food and has been observed off the west coast of North America, Baja California, Hawaii, and Japan. It’s scientific name, Tiburonia granrojo, comes MBARI's ROV Tiburon. More about deep ocean exploration can be found in our deep sea overview.

Sea Whip Coral

Credit: Aquapix and Expedition to the Deep Slope 2007The pink strands of this single deep-sea coral harbor a variety of marine life. Sea whips are gorgonian corals and have flexible skeletons. See more pictures of coral in our Deep-sea Corals article.

Fangtooth Fish

Credit: © David ShaleThis aptly named fish (Anoplogaster cornuta) has long, menacing fangs, but the adult fish is small, reaching only about 6 inches (17 cm) in length. It's teeth are the largest in the ocean in proportion to body size, and are so long that the fangtooth has an adaptation so that it can close its mouth! Special pouches on the roof of its mouth prevent the teeth from piercing the fish's brain when its mouth is closed.

It has been found as deep as 5,000 meters (16,404 feet), making it one of the deepest living fish, but is most common between 500 and 2,000 meters (1,640 and 6,562 feet). During the day it stays in deeper areas of the ocean and at night, migrates up to shallower water to feed. (This is called a diel migration.) Younger, smaller fangtooth fish filter zooplankton from the water and adults feed on fish and squid.

See more bizarre-looking ocean life in the Creepy Critters Marine Life slideshow and learn more in the Deep Ocean Exploration section. You can see a fangtooth specimen on display in the Sant Ocean Hall at the National Museum of Natural History.

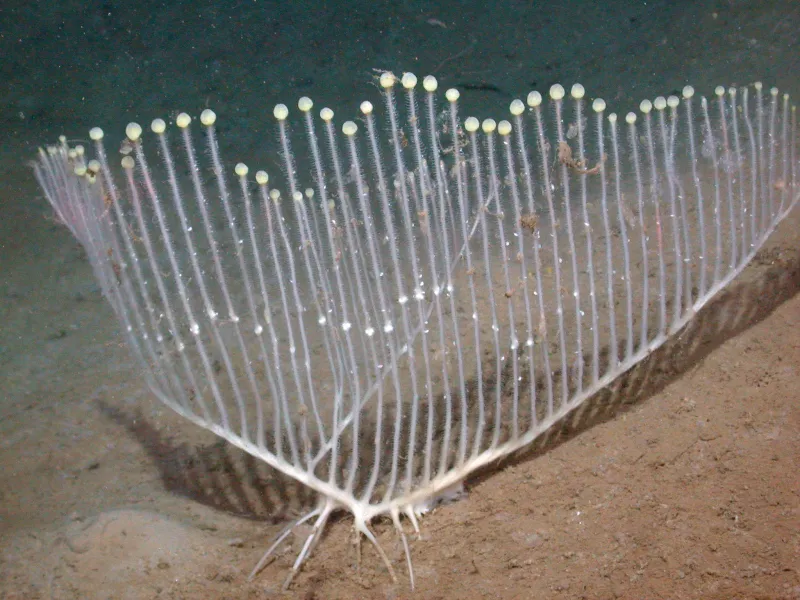

Venus Fly-Trap Anemone in the Gulf of Mexico

Credit: I. MacDonald (in Gulf of Mexico–Origin, Waters, and Biota. Vol. 1. Biodiversity. Felder, D. L. and Camp, D. K. (eds.) 2009. Texas A&M Press.Like its terrestrial namesake, the Venus fly-trap anemone (Actinoscyphia sp.) sits quietly and waits for food to drift into its outstretched tentacles, which are lined with stinging harpoons called nematocysts. Of course, this is how most anemones behave; this one just happens to look a like like the Venus fly-trap plant! They are deep-sea animals; this one was photographed at roughly 4,900 feet (1500 meters) by researchers with the Census of Marine Life. See more photos from the Census of Marine Life.

Spiny Deepsea King Crab

Credit: © David ShaleThis crab (Neolithodes sp.) was collected on a NOAA/MAR-ECO cruise to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the summer of 2009. Its red color provides camouflage and protection from predators. Red wavelengths are strongly absorbed by water, so red light does not normally reach the midwater ocean zone. Most deep-sea animals have lost the ability to see red. More about deep ocean exploration can be found in the Deep Ocean Exploration section.

Tubeworms on a Hydrothermal Vent

Credit: ©2003 MBARIRiftia tubeworm (Riftia pachyptila) colonies grow where hot, mineral-laden water flows out of the seafloor in undersea hot springs—such as the Guymas Basin of the Gulf of California at 2,000 meters (6562 feet), where MBARI took this photo. As volcanic activity deep below the seafloor changes, sometimes these hot springs stop flowing. In this case, the entire worm colony may die off. But new hot springs appear in other areas, and these are colonized by tubeworm larvae within a year or so. Marine biologists at MBARI are studying how rapidly the tubeworms can colonize new hot springs, which may be dozens or hundreds of miles from the old ones. Listen to a podcast about Riftia from One Species at a Time.

Deepsea Lizardfish

Credit: © David ShaleThis lizardfish (Bathysaurus ferox) rests on the ocean bottom with its head slightly elevated—waiting to snatch prey with its large mouth and sharp teeth. It lives at depths of 600-3,500 meters (1,969-11,483 feet) and grows up to 64 centimeters (25.2 inches) long. More about deep ocean exploration can be found in the Deep Ocean Exploration section.

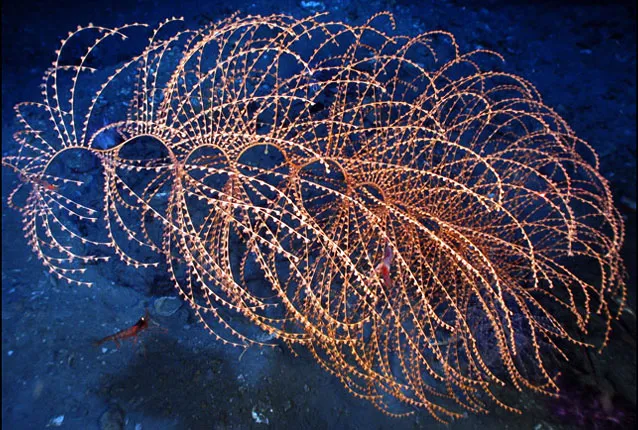

Harp Sponge

Credit: Copyright © 2005 MBARIThis newly-discovered carnivorous sponge (Chondrocladia lyra) was found using robotic submersibles operated by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute 10,000 feet below the surface in dark waters. It traps small crustacean prey with barbed hooks found along its branch-like limbs. Once it has caught something, the sponge covers it with a thin membrane and the digestion process begins.

Phronima

Credit: © David ShaleThis tiny, shrimplike creature is no more than 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) long, but it’s as ferocious as a shark. Its giant eyes spot prey. Huge claws grab the prey, and a tiny mouth rips it to shreds. The prey never sees what’s coming, because Phronima’s transparent body blends into the surrounding water. More about deep ocean exploration can be found in the Deep Ocean Exploration section.

Bubblegum Coral

Credit: NOAA/MBARI 2006This bubblegum coral (Paragorgia arborea) has a fanlike shape. It is growing 1,310 m (4,298 ft) deep on the Davidson Seamount southwest of Monterey, California. Learn more about deep-sea corals in the multimedia feature "Coral Gardens of the Deep Sea."

Bioluminescent Octopod

Credit: Michael Vecchione/NOAAThe yellow bioluminescent ring on this female octopus (Bolitaena pygmaea) may attract mates. Bioluminescence is an important adaptation that helps many deep sea animals survive in their dark world. More about deep ocean exploration can be found in our Deep Ocean Exploration section.

A Striped Deep Sea Worm

Credit: © Hauke Flores, AWIIn Antarctica's Southern Ocean swims a beautiful polychaete (bristly worm) called Tomopteris carpenteri, which is adorned with alternating red and transparent bands. The largest species in its genus, it it found throughout the water column, including the deep sea, where this photo was taken by Census of Marine Life researchers. Most polychaetes swim in the open water using their parapodia, the comb-like appendages coming off their sides, but some bury into the seafloor. Many members of the Tomopteris genus are bioluminescent and can shoot sparks off their parapodia when threatened.