“Upon returning from the reef after a night dive, I swam toward a bright reflection and came eye-to-eye with this beautiful, curious squid," says Nature's Best photographer Charles Viggers of this squid he photographed in the Cayman Islands. Squids have organs in their skin called chromatophores that reflect light and can change color to help them blend into their surroundings, attract mates—or attract photographers.

Stunning Squid Pictures

From the giant squid to microscopic squid babies, squids are beautiful and fascinating. As cephalopods, the same family as octopuses and cuttlefish, they have no bones, and swim head-first through the water with their 8 arms (and a pair of tentacles, in some species) trailing behind them. Some squids are brilliantly colored, with the ability to change the color of their skin to communicate, attract a mate, or defend against predators using chromatophores. They swim by jet propulsion, shooting seawater from a funnel, and some squids can even fly out of the water! Click through this slideshow of underwater photos of squids to see some of their stunning diversity.

Squid at Sunset Reef

Credit: Charles Viggers/Nature’s Best Photography

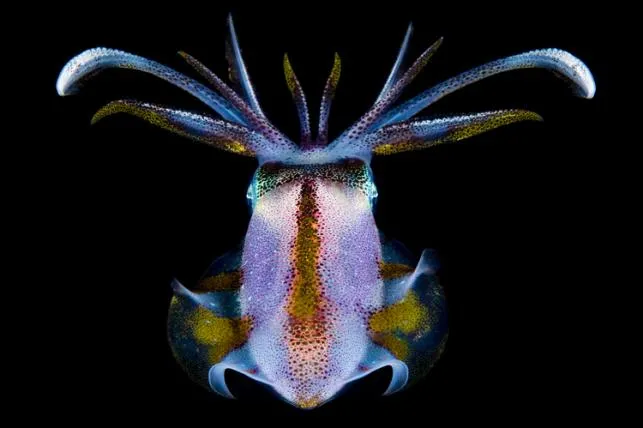

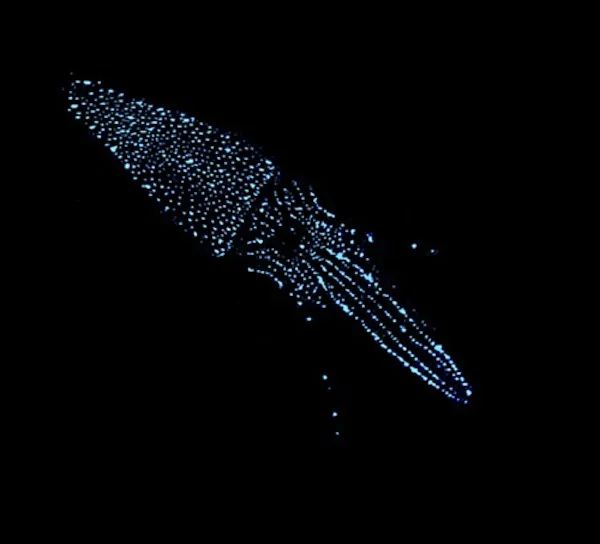

Jewel Squid

Credit: David Shale/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeThe “jewels” covering the body of this beautiful jewel squid (Histioteuthis bonnellii) are bioluminescent photophores. But these squids can't bargain for their lives with those jewels: they have been found in the stomachs of sperm whales, swordfish and sharks.

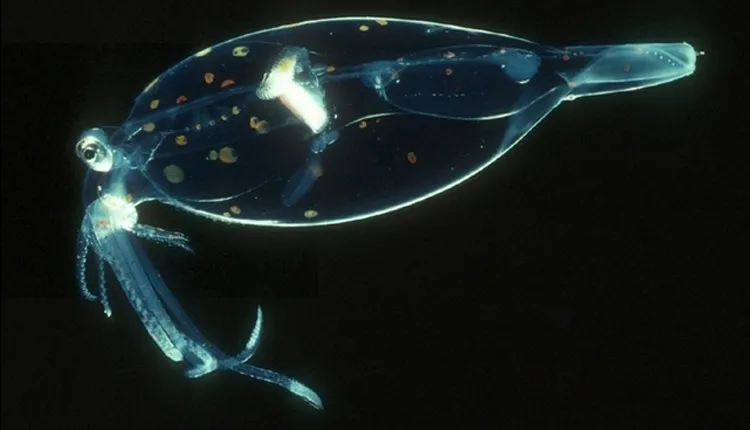

Cockatoo Squid

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeThis transparent cockatoo squid, or glass squid, retains liquids, giving it a balloon-like shape and helping it float. It has large eyes to see in the deep sea where it lives, and pigment-filled cells (chromatophores) that look like polka dots and serve as camouflage.

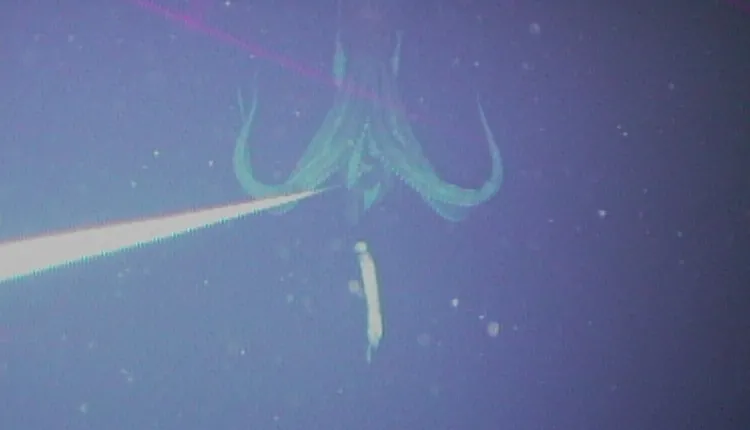

First Giant Squid Photographed in Natural Habitat

Credit: Tsunemi KuboderaThe first live photo of a giant squid in its natural habitat was taken in 2004 by two Japanese researchers who had suspended a long line from their research vessel with a camera and bait attached.

First Giant Squid on Video

Credit: Tsunemi Kubodera of the National Museum of Nature and Science of Japan/AP

First Giant Squid Filmed Live in Natural Habitat

Credit: NHK/NEP/Discovery Channel

Jumbo Squid (aka Humboldt Squid)

Credit: Brian Skerry, National GeographicA humboldt squid (aka the jumbo squid) releases a cloud of ink at night in Mexico's Sea of Cortez. These large, carnivorous squids can reach more than 5 feet in length and travel in shoals of 1,000 squids. Although they have historically been found in the Pacific off the coast of Mexico, warmer and more oxygen-poor waters caused by global warming have allowed them to expand their range northward up the western coast of the United States.

Armhook Squid

Credit: Hidden Ocean 2005, NOAA

Midwater Squid

Credit: E. Widder, ORCA, www.teamorca.orgGlowing photophores are visible on this midwater squid (Abralia veranyi) viewed from below at low light levels. We think of light as a way to see in the dark. But many species use it to help them hide. This adaptation is called counterillumination. Seen from below, an animal might stand out as a dark shape against the brighter water above. By glowing on its underside, it can blend in.

California Market Squid

Credit: © Brian Skerry, www.brianskerry.comTwo California market squids (Loligo opalescens) mate in the waters off of California's Channel Islands. While spawning, the male's arms blush red as he embraces the female, a warning to other competing males to back-off. Find out how and why squids and other cephalopods change color.

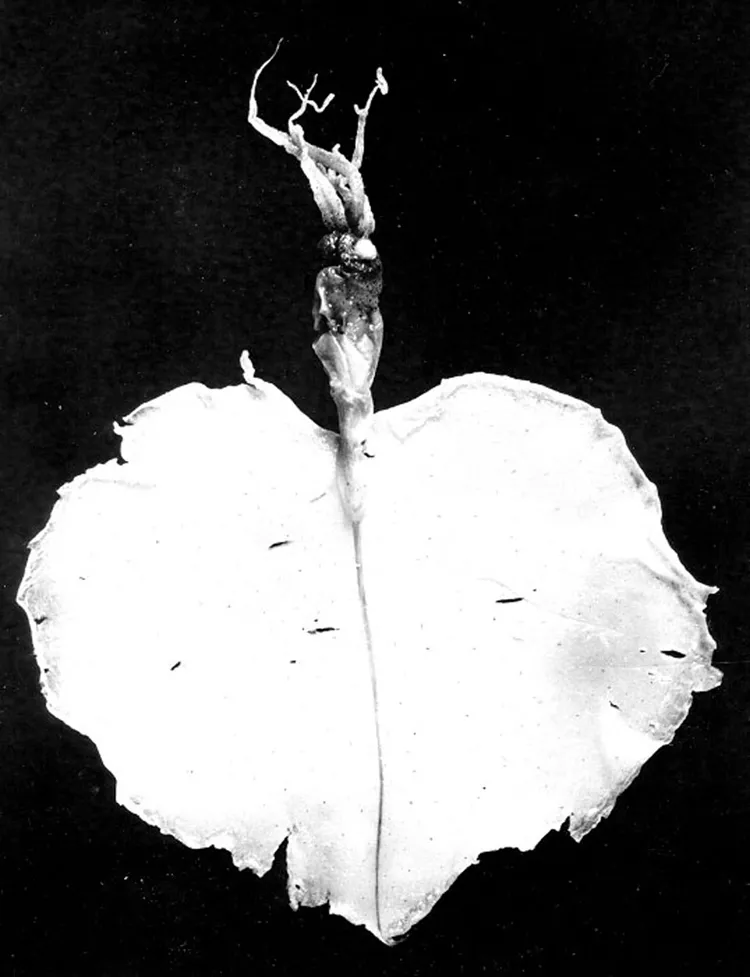

Arrow Squid Embryo

Credit: ©Clyde F.E. RoperSmaller than the head of a pin, this arrow squid (Doryteuthis plei) embryo looks like a miniature adult and is almost ready to hatch! Depending on the squid species, the development from a fertilized egg to a nearly-hatched larva can take one or several weeks. The embryo grows in its own egg-sac, which keeps it separate from other developing embryos nearby and provides it food. Once the yolk sac breaks, the new larvae will drift in the ocean waves as zooplankton. And if it's lucky enough to not be eaten by a predator, it will continue growing into an adult squid.

Arrow Squid Babies

Credit: ©Clyde F.E. RoperThese newly hatched arrow squid larvae (Doryteuthis plei) are each tinier than the head a pin. Free from their yolk sac, they will drift with the current out to sea as zooplankton. Many animals eat zooplankton, so few will survive to adulthood and to reproduce themselves.

Larval Squid, Coast of Kailua Kona, Hawaii, USA

Credit: Joshua Lambus/Nature's Best Photography

Bigfin Squid Specimen

Credit: Stillman BerryIn 1954 Smithsonian researchers dissected this squid specimen from the stomach of a lancetfish and added it to the Museum’s squid collection. Almost 50 years later, it helped scientists identify a strange, mysterious squid spotted in the deep ocean and describe a new family of squid—the Magnipinnidae or bigfin squid. More about deep ocean exploration can be found in our Deep Ocean Exploration featured story.

Squids and Cephalopod Diversity

Credit: © 1996 (1), 1996 (2), 1996 (3), 1996 (4), 1998 (5), 1996 (6), 1996 (7), 1996 (8) R. E. Young, Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory (2), Mark Norman (3), David Paul (4), Mark Norman (5), Thomas Burch (6), R. E. Young (7), R. E. Young (8)These Pacific cephalopods illustrate the wide diversity among this group of mollusks. You can learn about a relative, the giant squid (Architeuthis dux), in our Giant Squid section.