Tunicates—Not So Spineless Invertebrates

There are thousands of marine invertebrate animals in the ocean, from small to large, and in all shapes, sizes and colors. Some of these, like the shrimps and snails, are well known to us, but many invertebrate groups are not familiar to most people. One of these invertebrate groups—the tunicates—should be of special interest, however, because they are our closest invertebrate relatives.

About 3,000 tunicate species are found in salt water habitats throughout the world. Although tunicates are invertebrates (animals without backbones) found in the subphylum Tunicata (sometimes called Urochordata), they are part of the Phylum Chordata, which also includes animals with backbones, like us. That makes us distant cousins.

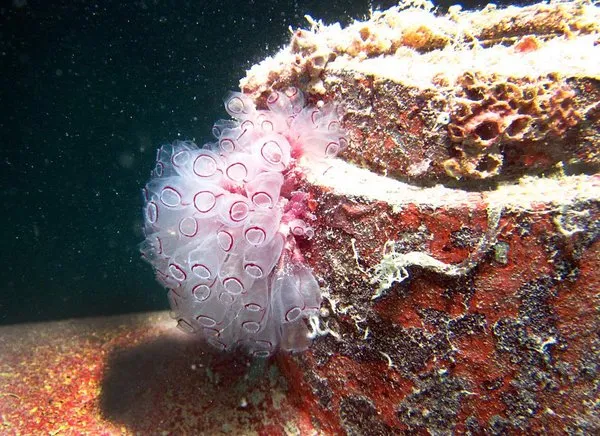

The most common tunicates are sometimes called sea squirts because when touched or alarmed by a sudden movement, their muscles contract and the water in the animal shoots out. They are sessile after their larval stage, meaning that they remain attached to a hard substrate, such as dead coral, boat docks, rocks or mollusk shells, all of their adult lives. The name “tunicate” comes from their outer covering, called the tunic, that protects the animal from predators, like sea stars, snails and fish. Unlike the sessile sea squirts, other kinds of tunicates float in the water their entire lives. The salps and pyrosomes are mostly transparent tunicates that look a bit like jellyfish floating freely—some pyrosomes have be known to reach 60 feet (18 m) in length. Much smaller but still visible to the naked eye are the larvaceans—tiny tadpole like creatures that live inside a small house that they build and regularly replace.

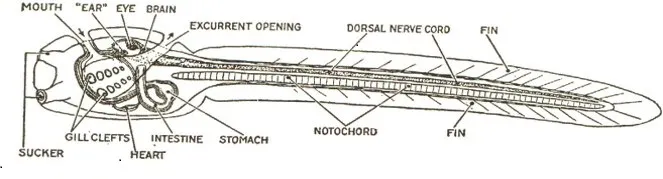

What unites these diverse groups and makes them our relatives? All animals in the Phylum Chordata have a notochord, a flexible backbone like structure, at some point in their lives.

Sea squirts have a notochord only in the larval stage which they use to swim and find an ideal place to attach—one that is bathed in particle-rich waters, since like all tunicates they are filter feeders and rely on water currents for food and nutrients. Once a good location is found, the larva attaches with a suction-like structure and metamorphosis begins. The notochord shrinks and gets absorbed into the body as the animal changes into an adult, and the tunic forms as the transformation occurs. The animal will then spend its days feeding on tiny particles from the water, primarily bacteria.

There are two types of sea squirts: solitary and colonial. The solitary animals live separately all of their lives inside of their tunics. Each has two siphons—the oral siphon that receives the nutrient rich current and the atrial siphon that excretes the waste. Colonial species share a common tunic and sometimes also share the atrial siphon. Colonies of sea squirts are formed as a result of budding—when the larva settles and changes into the adult form, it then splits (or buds) to produce new individuals, called zooids. Colonies can be a few centimeters to several yards wide depending on food availability and predation.

Sea squirts don’t look much like us as adults on the outside, but they have a digestive system similar to ours—with an esophagus, stomach, intestines and a rectum. But there are plenty of other differences. Unique to the benthic tunicates is a heart that reverses its beat periodically. It’s still a mystery to researchers why the tunicate heart will circulate blood through the heart in one direction and then switch to the opposite direction, or if the ability gives them some sort of advantage.

On land, we don’t encounter sea squirts that often, although they are increasingly eaten by some Mediterranean, Asian and South American countries. Not only is the soft body inside of the tunic eaten, but the tunic itself can be pickled and enjoyed later. Compounds from several tunicate species could be useful in medical treatments for diseases ranging from cancer to asthma. Tunicates act as ocean purifiers, since they consume bacteria, and they can send a message that heavy metals are present in ecosystems where they are found, since they absorb metals like zinc and vanadium. Because they like to attach to hard surfaces, sea squirts are often found on the underside of boats, or inside motors, where they can wreak havoc on equipment, and some have become invasive species after being transported from their native ranges. Their relatives the pyrosomes, also called sea pickles, sometimes wash up in large numbers on the shore and are known for their bioluminescence.

Like with many a large family, most of us don’t know about these distant relatives found in the ocean, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t worth keeping an eye on.