A Gray Whale Makes its Way to the Smithsonian

The transfer of an Atlantic gray whale skeleton from UNC Wilmington to the Smithsonian is making waves, and promising new insights into the lives of these marine mammals.

Gray whales undertake one of the longest migrations of any mammal, traveling upwards of 10,000 miles through the ocean annually. This particular one, however, traveled 381 miles along the open road. Arriving in November 2021 at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) from the University of North Carolina Wilmington (UNCW), the whale in question is one impressive specimen. It's the most complete recorded skeleton of an Atlantic gray whale, and its addition to the National Museum of Natural History Paleobiology collections will help scientists illuminate some of the mysteries of this marine mammal.

“The whole point is to save past worlds," said Dr. Nicholas Pyenson, Curator of Fossil Marine Mammals at NMNH. Awed by the specimen when he first saw it in UNCW's teaching collection three years ago, he facilitated its accession, along with Alyson Fleming a Research Associate at NMNH and faculty member in UNCW’s Department of Biology, who coordinated the documentation of the skeleton and first proposed its accession to the team. Pyenson expands, "I knew it was something different. Specimens like these, tie to place and time. They tell us how the world once was." And this skeleton, clocking in at about 1,000 years old after it was radiocarbon dated, could tell us about a very elusive time— when gray whales still widely swam the Atlantic.

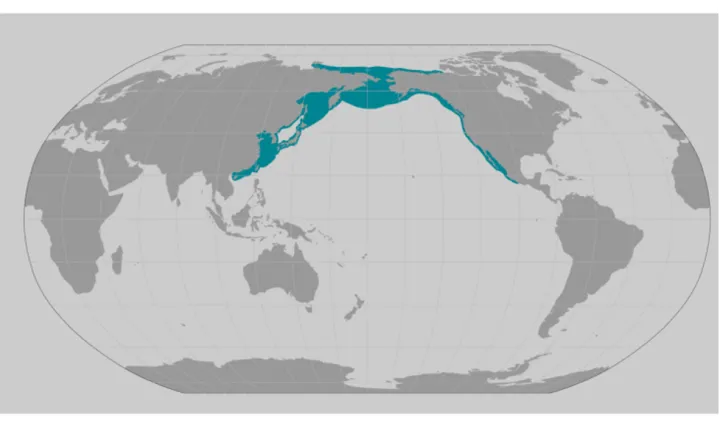

Up to 49 feet and 90,000 pounds, gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) are a species of baleen whale that were once found throughout the Northern Hemisphere. A number of factors contributed to their disappearance from the Atlantic Ocean, though researchers are still pinning down the why and when. Proximity to shorelines along the eastern U.S. made them a potential target for 17th and 18th century whaling, though they were never as viable a commercial species as the neighboring North Atlantic right whale. Ultimately, gray whales had largely disappeared from the Atlantic by the early 1700s, and the last recorded sighting of one took place around 1740. Nowadays, their population is mostly restricted to the North Pacific Ocean.

Chances to study an individual like this at length are few and far between, most of what’s previously been found of Atlantic gray whales are single bones—so a skeleton as complete as the one from UNCW can paint that much clearer of a picture—revealing insights into the past environments it belonged to and the behaviors of the species at that time. Consisting of 42 bones including the skull, jaws, appendages, ribs, and vertebral column, the skeleton is that of a one- or two-year-old whale, an age evidenced by the fact its skull hadn’t yet fused. This knowledge, combined with information about present day whales, indicates it may have been a young adult traveling south to breeding grounds. Each of the juvenile’s bones needed to be numbered once the specimen reached the Smithsonian’s collections—but before that could happen, it had to make quite the journey. A journey whose most recent leg began at UNCW’s vertebrate zoology collection.

“It was nifty, and very well organized,” recounted David Bohaska, the Smithsonian vertebrate paleontology collections specialist who was on site for the transfer alongside fossil preparator Peter Kroehler. “The pieces I usually work with are small. Even a juvenile gray whale is far bigger than I’m used to dealing with.” According to Bohaska, the transfer required all hands on deck, from those at UNCW to Smithsonian’s Registrar’s Office, Transportation, and a team affectionately nicknamed the “Move Crew.” “We got a van— it looked more like a minibus,” he shared, and when it came time to hop behind the wheel, the excitement and apprehension surrounding their mission only grew. “The whale was well protected: layers and layers of bubble wrap and tubes on tubes of padding.” They’d taken all the necessary safety precautions, but for Bohaska and Kroehler there was no forgetting the value, and the precariousness, of what they were carrying on their way D.C. “You’re going over a bridge on 95 and you’re noticing every single bump and seam. It adds a whole new layer of awareness to your handling of this marine specimen.” But with no shortage of care and some shortage of sleep, they managed to do it in three days. Once the gray whale had reached the Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center (MSC), it was time to unload it—an operation that would call for another team effort.

Smithsonian Paleobiology’s registrar Jessie Nakano handled much of the permitting and paperwork for the accession, and there was no shortage of boxes to check: “Because it’s a recently extinct marine mammal, it has unique specifications. We had to make sure we cross-checked with the Marine Mammal Protection Act.” But once the accession was squared away and the whale arrived, Nakano joined the party at MSC’s whale warehouse. According to her, the skull alone took four people and a rolling cart to carry in. “I’m usually working with million-year-old specimens, so it was really interesting being exposed to something more recent. And Nick & the people at UNCW’s fascination with it got me very excited about it as well.” Now, the skeleton is settling into its new home at the whale warehouse, laid carefully to rest on archival grade padding.

It proved quite the trip, but this Atlantic gray whale would’ve been well used to that. The yearling’s prolific lineage made many, many more. Before being given to UNCW, the bones were found by local residents along the North Carolina coast, and the location where the bones were uncovered points toward the yearling having once been part of a migration. “Calves are typically born in southerly latitudes, and they move north to feed” said Dr. Pyenson. This might be evidence of that phenomenon. As for what these whales were feeding on in the north, scientists are still piecing the full picture together. What they do know is that gray whales are venturing out from the North Pacific once more, with reports in the last decade suggesting they’re being spotted in the Atlantic again. “As for how they got there, it’s either through the Northwest Passage or south around Cape Horn,” hypothesized Dr. Pyenson.

As for Atlantic gray whales and their history, this skeleton will help researchers to fill in more pieces of that puzzle. “The thing about specimens like this, they’re only as valuable as their context, otherwise it’s all just bone and rock.” Dr. Pyenson reflected. The Smithsonian’s collections stewardship prioritizes that context, making sure the information about who found a specimen, where, and when is carefully saved with it. A study of the skeleton that was published in July 2022 indicates that it was likely partially submerged underground. One half of the skeleton shows signs of weathering, while the other shows damage from grass roots. There were also v-shaped notches indicating that animal was butchered. Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at NMNH who specializes in the evolution of the human diet, helped decipher the accessioned bones. Her work will help explore the marks found on the bones and hopefully answer questions about why people butchered the whale, and if the whale was actively hunted or scavenged.These bones undoubtedly have stories to tell, and thanks to the joint efforts of UNCW and Smithsonian, we'll be able to listen all the better.