Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Milestones

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico was the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history. With millions of gallons of oil spilled in the sea, the response effort was large and has lasted for over a decade. For over 10 years, scientists and researchers have come a long way in restoring, recovering, and researching the Gulf environment. While substantial progress has already been made, there’s still a lot to learn about the lasting impacts of oil spills.

Explosion of Deepwater Horizon

The BP Deepwater Horizon oil rig explodes in the Gulf of Mexico. This causes the wellhead of the oil rig to rupture, initiating the largest known oil spill in the United States. Eleven people die during the tragedy.

Boats trying to control the fire on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig. Credit: U.S. Coast Guard

Flushing oil away with freshwater

In an attempt to keep oil from coming into shore, Mississippi releases a levee to flush the area with freshwater. This freshwater influx is later linked to the loss of 8.3 million oysters along the Gulf shores of Louisiana.

Oysters were a significant part of Louisiana's economy, but after the oil spill, the oyster populations were devastated. Credit: Dispatches from the Gulf

Taking immediate action

In the days and weeks following the start of the spill, government agencies and scientists begin taking steps to mitigate the spread and impact of the oil. These steps include creating physical barriers with floating booms, using skimmers to remove oil from the water’s surface and the use of dispersants on and below the surface of the water.

Brown pelicans congregate on a containment boom a few months after the oil spill. Credit: Petty Officer 3rd Class Cory J. Mendenhall, U.S. Coast Guard

BP makes their pledge

BP commits $500 million towards researching the effects of the oil spill on environmental and human health. With this funding, an independent research organization called the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is formed. GoMRI funding is split among research groups, also known as consortia, that tackle overarching topics or research questions.

Workers contracted by BP load oily waste onto a trailer on Elmer's Island, Louisiana. Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Patrick Kelley

Hundreds of Health, Safety, and Environment (HSE) contract workers cleaned up oil from the Deepwater Horizon/BP oil spill. Credit: Petty Officer 3rd Class Patrick Kelley/U.S. Coast Guard

Assessing the damage

Eleven government agencies come together to form the Natural Resource Damages Assessment (NRDA) council. The council works to collect and assess data that will inform restoration planning and implementation.

Oil from the spill impacts the Louisiana coast. Credit: Office of the Governor of the State of Louisiana

Contaminated seafood causes fisheries closures

Soon after the spill, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) closes down fisheries due to the risk of contaminated seafood. Closures peak on June 2nd, with over 88,000 square miles of the Gulf closed to fishing.

A shrimp boat fishes in the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: Dispatches From the Gulf

Tar balls are traced back to the spill

All five Gulf states report tar balls washing up on shorelines. Testing confirms that these tar balls are the result of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Though BP performed some cleanup operations, tar continued to collect at the edge of the sand dunes, clinging to seashells and driftwood to form tar balls. Credit: Flickr user Geoff Livingston

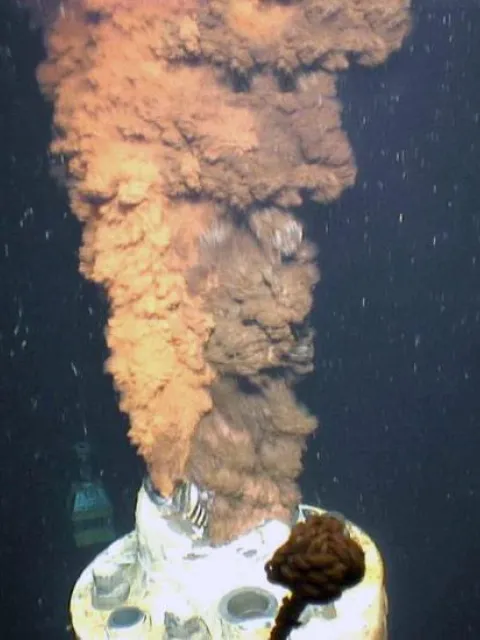

Capping off the well

Eighty-seven days after the initial explosion, the oil well is capped. By now, 130 million gallons of oil spilled into the sea. Measures continue in the attempt to permanently seal the leak.

Deepwater Horizon wasn't a surface spill; instead, oil spewed into the deep sea from the underwater wellhead. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

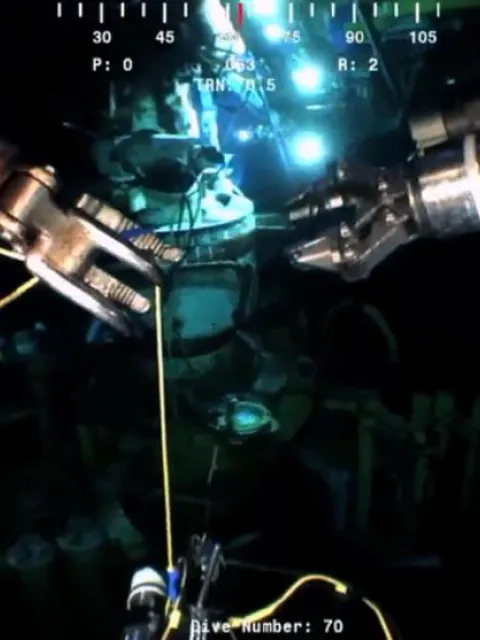

Woods Hole scientists operate an ROV to sample the oil spewing from the ruptured Macondo Well. Credit: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Doubting dispersants

There are reports of a 22-mile-long oil plume in the deep water around the wellhead where the spill occurred. Researchers find the chemical dispersants meant to help break up and wash away the oil may actually cause it to stick around.

A C-130 Hercules from the Air Force Reserve Command deploys dispersant into the Gulf of Mexico as part of the oil spill response effort. Credit: U.S. Air Force, Tech. Sgt. Adrian Cadiz

Permanently sealing the leak

BP announces they’ve officially sealed the wellhead, ending the flow of oil into the Gulf.

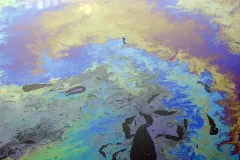

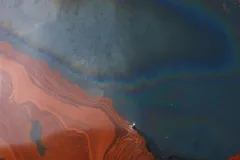

In this view of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill from above, you can see bright orange oil floating on the ocean's surface on the left and, on the right, a thin layer of oil reflects the colors of the rainbow. Credit: David Valentine, University of California Santa Barbara

Fisheries feel the effects

Sections of the Gulf are closed to shrimpers due to tar balls coming up in shrimp nets. These fisheries remain closed for much of the following year.

After the spill, shrimp fisheries in the Gulf were closed for the better part of a year. Credit: Flickr user J Jackson

Tiny critters reveal an ecosystem imbalance

Researchers studying tiny, hard-shelled, single-celled organisms known as foraminifera find that they’re on the decline following the oil spill. Also known as forams, these critters are an indicator species, meaning their community changes can signal an ecosystem imbalance.

In this photo of a shallow coral reef in the Pacific there are three species of forams. Their colors come from the symbiotic algae that live inside the foram shells. Credit: Pamela Hallock/University of South Florida

These are the shells of microscopic organisms called foraminifera, which build intricate shells from the calcium carbonate they collect while drifting through the water. Credit: Flickr User Mouser NerdBot

Researchers report ecosystems are rebounding

Just two years later, researchers are pleasantly surprised with how quickly ecosystems are recovering. Less oil sticks around than scientists predicted, in part because of oil-eating microbes from the Gulf’s seafloor. Scientists also note marsh grasses are rebounding well.

GoMRI researchers found that blue crab populations have actually grown since the oil spill. Credit: Flickr user jere7my tho?rpe

Tracing the source of an oil sheen

An oil sheen appears near the site of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Researchers studying the oil’s chemical makeup find this sheen is the result of oil from the 2010 spill, not from an active leak in the wellhead.

An oil slick from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Credit: Luke McKay

Drifters help to gather data

Researchers associated with GoMRI’s Consortium for Advanced Research on Transport of Hydrocarbon in the Environment, or CARTHE, deploy drifters to gather locational data. Collecting this data allows for researchers to accurately model surface and below-surface currents to predict how oil disperses once it’s spilled, helping to aid in future response efforts.

Researchers launch one-meter-tall plastic drifters into the Gulf. Over 300 of these drifters were released and their location information was sent to researchers every five minutes through GPS satellite. Credit: CARTHE

Impacts on sparrow reproductive success

Scientists find that sparrow populations in Gulf marshlands are experiencing changes in their reproductive success. Sparrows nesting on previously oiled marsh areas are successful in raising only five percent of their chicks to fledging.

With their brown and yellow markings, seaside sparrows (Ammodramus maritimus) blend in well with marshgrass. Credit: Philip Stouffer, Louisiana State University

Sabrina Taylor, a wildlife biologist at Louisiana State University and lead scientist for the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative, releases a seaside sparrow in the Louisiana marsh. Credit: Philip Stouffer, Louisiana State University

Understanding impacts on Gulf marsh grasses

Scientists studying the impact of the oil spill on marsh grasses along the Gulf waterline find that grasses growing in the outer marsh protect the inner marsh, leaving them largely untouched by oil. However, these oiled outer marsh areas erode twice as fast as non-oiled areas.

Dark brown oil floods a marsh on the Mississippi Delta after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Credit: NOAA

Dolphin strandings are on the decline

Dolphin strandings in the Gulf region began to rise after the 2010 spill. Over the next four years, researchers discovered over a thousand dolphins stranded and distressed along the Gulf Shore. This four-year period is recognized as the largest dolphin die-off in the Northern Gulf, but beginning in 2014 the number of stranded dolphins begins to steadily decline.

Striped dolphins observed in emulsified oil in the Gulf of Mexico, just a few days after the spill. Credit: NOAA

Scientists estimate seabird losses

Scientists collecting data about the impact of the oil spill on seabirds determine that a total of 93 different species of birds were affected. They estimate that 800,000 coastal birds and 200,000 offshore birds died as a result.

A brown pelican stands mired in oil. Credit: Office of the Governor of the State of Louisiana

Identifying dispersant alternatives

Researchers identify food-grade materials as an effective alternative for dispersants. These food materials include lecithin found in soybeans and Tween 80 found in ice cream.

Graduate students Danielle Young from Temple University and Dannise Ruiz from Penn State preparing oil and dispersant solutions for exposure experiments with deep sea corals. Credit: Erik Cordes

A settlement is made

BP and others are held responsible for the spill. They agree to pay a $20.8 billion settlement, with $8.8 billion going towards damages to natural resources. This is the largest environmental damages settlement in US history.

Oceana's Pacific Science Director Jeff Short collects samples of mousse oil in the Gulf of Mexico from the Deepwater Horizon spill. Credit: J. Short, Oceana, and S. Senner, Ocean Conservancy

Understanding the effects on fish

Researchers look at the effects of the oil spill on fish, finding that certain fish species have adverse heart effects after exposure to even low levels of oil. They find that the heart of Mahi Mahi stops working efficiently as soon as 24 hours after exposure. Researchers also find that juvenile fish experience heart problems and behavioral defects when exposed to crude oil.

Gulf killifish are small and abundant, making them an excellent study species for scientists looking to understand the effects of oil on fish health. Many GoMRI projects feature killifish, including ones looking at genetics and embryonic development after oil exposure. Credit: Andrew Whitehead

Scientists find seafood chains are largely unaffected by dispersants

The National Academy of Science finds that fish and shellfish contain very low concentrations of dispersant chemicals, meaning the impacts of dispersants on seafood are extremely low.

Scientists await a net as it is hauled back on deck. Credit: DEEPEND

Restoration Begins on the Gulf of Mexico Seafloor

Almost 10 years following the spill, some restoration efforts are just getting underway. Four restoration projects aimed at restoring deep sponge and coral habitats injured by the spill are announced. In total, $126 million in restoration funds are allotted to these projects to help restore marine resources in the Gulf of Mexico.

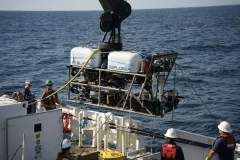

Oceaneering International’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) being lifted from the deck of the NOAA ship Nancy Foster. (NOAA, University of Rhode Island Inner Space Center)

Scientists develop a fish vulnerability index

Researchers create a framework to assess different species' responses to their environment, helping to identify which fish will be most vulnerable after a spill. This will allow researchers to respond to the most at-risk species in the event of future spills.

Black grouper are commercially fished in the Gulf of Mexico and one of the fish species vulnerable to oil spills according to the vulnerability index. Credit: NOAA National Ocean Service

A group met in Cuba to develop a framework for identifying what fish traits to measure related to oil exposure. Credit: Beth Polidoro

Midwater species likely harmed by oil spill

A study indicates dramatic losses in midwater sea life, likely due to the oil spill. Compared to 2011, the shrimp population numbers during the 2015/2016 season decreased by about half, squid populations decreased two-thirds, and fishes were down about 75 percent. But the biggest decline came from two of the most important food sources for large marine animals. The “anchovies of the open sea,” a group called lanternfishes, decreased over 80 percent, and krill, the favorite food of large whales, decreased by over 90 percent.

A beautiful orange colored copepod from the deep sea in the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: Danté Fenolio

An oceanic ray-finned fish called the hatchetfish. These hatchetfish were found in the deep sea of the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: Danté Fenolio

Smithsonian Scientists Aid in Restoration

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History joins forces with NOAA and the Department of the Interior to help restore deep sponge and coral communities injured by the spill. Invertebrate zoology curators and scientists help provide taxonomic and genomic expertise to better understand these communities before and after the spill and to inform restoration activities.

Invertebrate specimens in the Smithsonian NMNH wet collection. The Museum’s collection which currently houses over 50 million specimens will help scientists understand what deep sea sponge and coral habitats were like in the Gulf before the spill. (Smithsonian NMNH)

May 2023

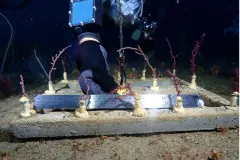

About 200 fragments of octocorals were transplanted from larger colonies to the seafloor 230 feet (70 meters) below the surface to test what types of restoration techniques will be the most successful at replacing the corals that were lost due to injury from the spill. After two months in their new location, over 95% of the transplanted corals were still healthy and surviving in their new home.

Fragments of deep water coral are placed on a coral outplanting rack and monitored by scientific divers. (Marina Bozinovic/California Academy of Sciences)