Hope & Despair for the North Atlantic Right Whale Population

Late one afternoon in February 2019, Melanie White and the other members of a highly trained aerial survey team were nearing the end of their almost eight-hour flight off the Georgia coast when they finally discovered what they had been hoping to see for weeks. The team, from the Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, began their near-daily search flights in December scanning the Atlantic Ocean from an altitude of a thousand feet for what White described as “a disturbance, a black body, a spout, anything that would trigger our eyes….” On this day the “disturbance” they spotted in the ocean below was a female North Atlantic right whale named Pico and her newborn calf—the seventh discovered during a birthing season that occurs in warm waters off the coast of Georgia and Florida from mid-November to mid-April. The seven newborn calves spotted in 2019 by this team, and others, represent a rebound from the previous season when no calves were born, but concern for the species remains.

North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) are among the most endangered of all large whales. The North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium’s recent Report Card revealed the best estimate of the population at the end of 2017 was 411, down from a 2016 estimate of 451. Amy Knowlton, a senior scientist with the New England Aquarium and a pioneer in studying right whales said in an interview, “it’s encouraging to see calving get going again,” but added, “we’re still losing ground.” Tim Gowan, a research scientist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute and a member of its right whale team explains: “We would need at least 12 calves per year, half being female, for the population to remain stable, and more for the population to increase.” The Consortium’s 2018 Report Card warns that the declining birth rate combined with an “unprecedented” twenty right whale deaths during 2017 and 2018 “threatens the very survival of the species.”

The feeding and migratory habits that made these behemoths the ‘right’ whale to hunt, and led to their near extinction by the early 1800s, are today exposing them to increased dangers from fishing activity and busy ship traffic along the eastern seaboard of the U.S. and Canada. Mark Baumgartner, Chair of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium says, “Adult right whales don’t die of old age. They die from human-caused mortality, fishing gear entanglements, and ship strikes.” As a result, Baumgartner said North Atlantic right whales now tend to die between the ages of 20 to 30, instead of a projected lifespan of at least 60 to 70 years.

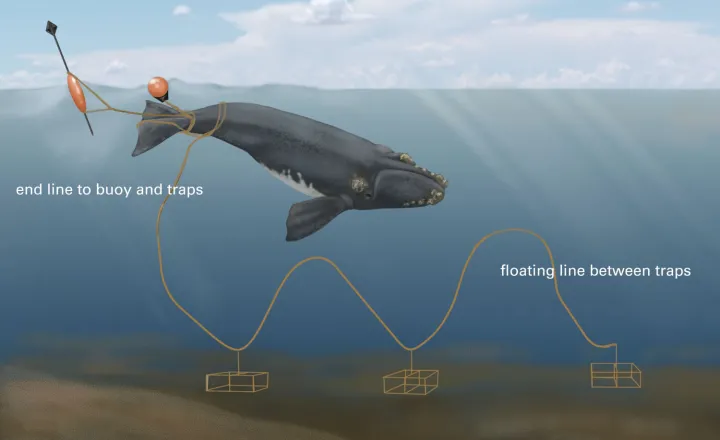

During spring and summer right whales often find their favorite food—tiny and nutritious crustaceans called copepods—in the same busy waters where fishers drop their lobster traps and snow crab pots to the seafloor. Ropes connect lobster traps together in a string or “trawl” and additional ropes attach the trawl to buoys at the surface. Snow crab fishers send their pots to the bottom one by one and each is roped to a surface buoy.

A 2018 report from NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center estimates more than one million vertical lines are deployed along right whales’ migratory routes, calving grounds, and foraging areas stretching from Florida to New England and Canada. The same report cites research showing 85 percent of right whales have been entangled at least once and 57 percent at least twice. Examination of dead right whales and photographs of living right whales show ropes from fixed fishing gear slicing through mouths, wrapping tightly around whales’ bodies, and causing deep internal injuries.

Right whales that manage to escape from ropes, or are freed by special whale rescue teams, exhibit scars and lasting injuries that lead to poor health, shorter lives, and for females, fewer births. “You severely entangle a right whale, it might throw [off] the gear but it will not recover to be fully strong again for a year or maybe two years and we see it in the calving data. A female who gets entangled ceases reproduction for a couple of years until she gets fat again,” explains Scott Kraus, Vice President and Chief Scientist for Marine Mammals at the New England Aquarium.

In addition to direct threats from gear entanglement and ship strikes, right whales must now spend more energy finding new areas to feed because warming water temperatures are disrupting the development of copepods in their traditional habitats. The extra demands of foraging in new areas extends the time between females’ pregnancies and stresses the entire population. “Right whales, in one sense, are the first large whale that’s really showed changes in behavior, abundance, and distribution due to climate change,” Kraus says.

Right whales searching for food arrived in force in the cold waters of Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence early in the summer of 2017. There, they encountered an estimated 45,000 ropes, each connected to a snow crab pot. Expecting a rich harvest, the Canadian government had allowed twice as many pots and lines as the previous year. The whales also arrived in the midst of the busy season for large cargo vessels and cruise ships. The result was an alarming twelve right whale deaths. Surprised Canadian authorities rushed to close a large section of the Gulf to fishing and ordered ships to slow down. More permanent protections were implemented, similar to U.S. regulations that had been introduced in stages since 1997, which seemingly prevented additional right whale deaths or injuries in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 2018.

Research and new technologies fostered by a collaboration of more than 100 scientists, conservationists, government and industry officials who are members of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium offer hope that a better future awaits the seven calves born this winter. Expanded use of underwater listening devices that detect whales’ calls will provide information about whale migration and early warning of whales’ presence so that protective measures can be established. In pilot projects, Canadian and New England fishermen are testing “ropeless” fishing gear that eliminates the maze of ropes connecting traps and pots to the surface by keeping the retrieval rope submerged with the gear until it receives a signal from the fishing boat. Amy Knowlton leads a team investigating new kinds of rope and connecting sleeves strong enough to pull up pots and traps, but come apart under the strain of a whale. Beth Casoni, Executive Director of the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association, says her members are testing new equipment and “willing to do more” to protect right whales.

Scott Krause remains optimistic: “[Right whales] will figure out the food thing, they will figure out reproduction, and they will be able to come back from this. We just have to stop killing them with ships and fishing gear.”